Prayers have to be real

Jesus told a parable to people who “trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt.”

Aren’t we lucky that we know better than to act that way? We might even say, “We thank you, God, that we’re not like those people.”

Oops.

Because of course, Jesus is talking to us. To the religious. To the reliable. To those who come to church on Sunday morning and occasionally dare to think we have things figured out.

“Two men went up to the temple to pray.” Every one of Jesus’s listeners would have been able to picture the scene. The temple was the heart of Jerusalem, and the heart of the Jewish faith of Jesus’s time. Its construction was one of the great accomplishments of the ancient world. Vast stone courts, imposing walls. And it was a place full of life — the shuffle of sandals, a low hum of prayer. There were outer areas that served as gathering places, open to all. But the ground became ever more sacred, ever more restricted as you moved inward. And at the center was the Holy of Holies, in some sense God’s dwelling place on earth, entered only once a year and only by the high priest.

“Two men went up to the temple to pray.”

The first was a Pharisee. A religious leader. Careful in his observance. The sort of person others trusted to interpret Scripture or settle disputes. A rule follower. A good man.

The second was a tax collector. A collaborator with Rome. Despised for the corruption, greed, and betrayal that were part and parcel of his profession. A bad man.

Two very different men. But both came to the holy place. Both offered their prayers to God.

The Pharisee stands where he’s entitled to stand: near the center. His posture is confident. His words practiced. He has nothing to be ashamed of — and he knows it. “God,” he says, “I thank you that I’m not like other people — thieves, rogues, or even like this tax collector.”

And he’s not wrong, is he? He’s the sort of person we might ask to serve on a Vestry or chair a stewardship campaign. In Episcopal Church speak, he’s what we call “a communicant in good standing.” In case you haven’t read our rule book lately, that’s anyone who “is faithful in corporate worship, unless for good cause prevented, and is faithful in working, praying, and giving for the spread of the Kingdom of God.”

The other man, the tax collector — he stands far off. He doesn’t dare approach the altar. He doesn’t lift his eyes. He just stands there, beating his breast, saying, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” No preface, no promises, no excuses.

Why does God hear one prayer and not the other?

There’s nothing wrong with the words the Pharisee uses. We should be grateful for all the blessings of our lives.

But we do the same sort of thing the Pharisee did all the time. Have you ever said, “There but for the grace of God go I”? On the surface, it sounds humble. And sometimes it is. Sometimes it’s a statement of profound and humble gratitude. But sometimes it’s just a polite version of, “I thank you that I’m not like them.”

The parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector made me think of a scene from Shakespeare. In Hamlet, King Claudius tries to pray after murdering his brother. But he gives up in despair because he knows he’s only going through the motions. He wants power far more than he wants God’s forgiveness. This is what he says: “My words fly up, my thoughts remain below; words without thoughts never to heaven go.”

I think the tax collector has three things that the virtuous Pharisee doesn’t have — three things that the evil Claudius doesn’t have. The tax collector is humble. He’s ruthlessly honest. And he knows that he needs God’s grace more than he needs anything else. The tax collector has three things that are really one thing: humility, honesty, and a need for God.

“All who exalt themselves will be humbled, and all who humble themselves will be exalted.” That’s what Jesus says.

It sounds like a warning, but it’s really a promise. Because God isn’t looking for opportunities to hurt us. God is waiting for the moment when we finally stop pretending.

The tax collector goes home justified, made right with God. Not because he earned it, but because he told the truth. And that’s all God ever seems to need: honesty makes space for grace.

So what does that mean for our own prayers? For how we ourselves connect to God?

We live in a world that rewards performance. But the prayer that reaches heaven isn’t polished. It’s just real. It’s the prayer that says, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.”

It’s a prayer that never ends in shame. It ends in grace. It’s a prayer that God never answers with a “no.” A prayer for mercy that God always hears.

And we should remember that the same God who heard a man’s trembling words in the temple courtyard is listening still. Listening for truth. For humility. For the smallest crack in our armor — a crack where mercy can enter in.

So if your prayers ever feel awkward or thin, stop looking for the right words. Just tell the truth. Your prayers don’t have to be perfect. They just have to be real.

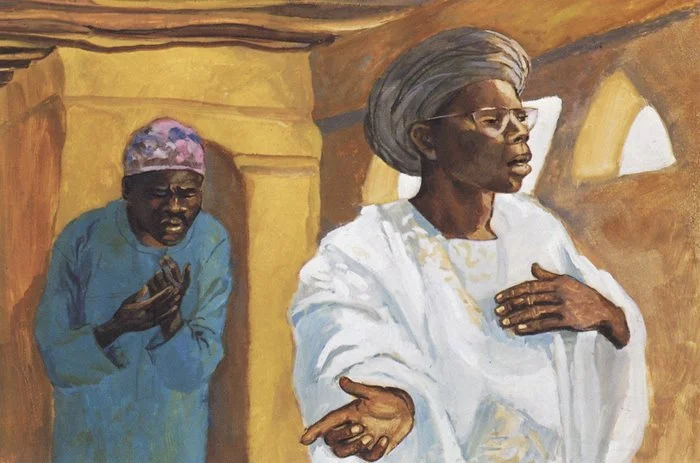

About this image: “Although this work is directly associated with the Luke 18 passage, it is very similar to the Matthew 6:1-6 passage as well. JESUS MAFA is a response to the New Testament readings from the Lectionary by a Christian community in Cameroon, Africa. Each of the readings was selected and adapted to dramatic interpretation by the community members. Photographs of their interpretations were made, and these were then transcribed to paintings.”

Attribution: JESUS MAFA. The Pharisee and the Publican, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48268[retrieved October 31, 2025]. Original source: http://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr (contact page: https://www.librairie-emmanuel.fr/contact).